In this column, members of the editing community share what’s on their (physical) bookshelves and highlight a few notable titles. In our previous instalment, editors shared such treasures as Writing for Busy Readers: Communicate More Effectively in the Real World by Todd Rogers and Jessica Lasky-Fink, and A Grain of Wheat by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. If you’d like to show us your bookshelf, or part of it, let us know!

Amanda Goldrick-Jones is a freelance editor who specializes in academic and business writing. Her bookshelf is in Victoria, British Columbia.

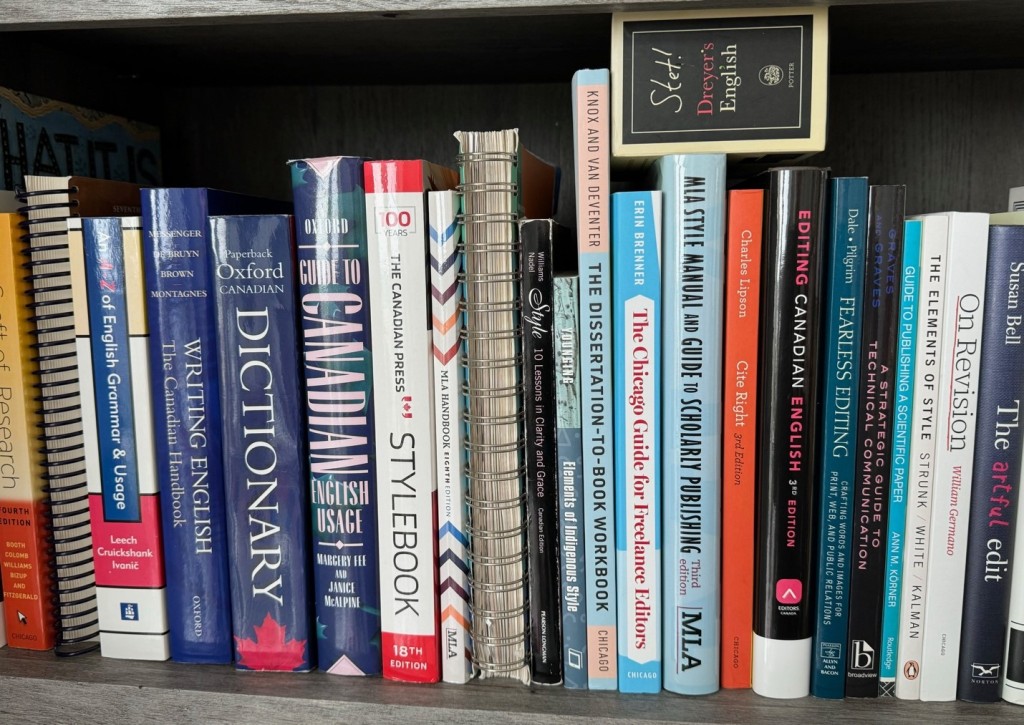

My bookshelf is stuffed with style guides, editing guides, books on plain language, and (what else?) Benjamin Dreyer’s game, STET! I also cling to my 20-year-old copy of the Canadian Oxford Dictionary. But I have a brand new, long-awaited copy of Erin Brenner’s recently published The Chicago Guide for Freelance Editors: How to Take Care of Your Business, Your Clients, and Yourself from Start-Up to Sustainability (2024). I’d have loved this when I started freelancing four years ago, but it’s never too late to learn—or continue to hone—sound, sensible practices for your freelance business. Brenner covers the entire range of strategies for starting and operating as a freelance editor: from discovering what motivates you to be an editor, to setting up your admin structure (including your rates!), to branding and marketing, to sustaining a successful business without burning out, and so much more. Browsing this book is like sitting down to chat with a friendly mentor who has your interests wholly at heart.

My other recent purchase from the University of Chicago Press is Katelyn E. Knox and Allison Van Deventer’s The Dissertation-to-Book Workbook: Exercises for Developing and Revising Your Book Manuscript (2023). In plain, friendly language, this guide ushers writers (and their editorial partners!) through a comprehensive developmental process, including how to articulate the book’s organizational principle and themes, and shape the book’s structure by posing and answering a series of questions. As an academic editor, I find this process usefully underscores how different a dissertation is from a book.

Previously mentioned in this column is one of my most treasured style guides: Gregory Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples (2018). Far from a checklist, this richly historical and cultural guide, published by Brush Education, situates respectful and accurate writing, editing, and publishing practices within an Indigenous-rights-based framework. On a personal note, I had the privilege of hearing Younging speak about his book at a conference in 2018, after which he signed my copy. His death in May 2019 was a tremendous shock.

Finally, a guide I treasure to the point where it’s almost falling apart is Joseph M. Williams’s venerable Style: 10 Lessons in Clarity and Grace, first published in 1995. I have the only Canadian version from 2004, but every edition—including the 13th (2020)—offers extensive examples and exercises that delve into what makes sentences and paragraphs clear, plain, and powerful. Though I sometimes find Williams’s avuncular tone annoying, Style offers invaluable strategies for turning dense, wordy prose into clear, engaging, and inclusive writing without sacrificing complexity. It’s one of my favourite resources for academic and professional writers.

Jackie Goutor is a fiction editor with a special interest in mysteries, science and speculative fiction, and fantasy. Her bookshelf is in Toronto.

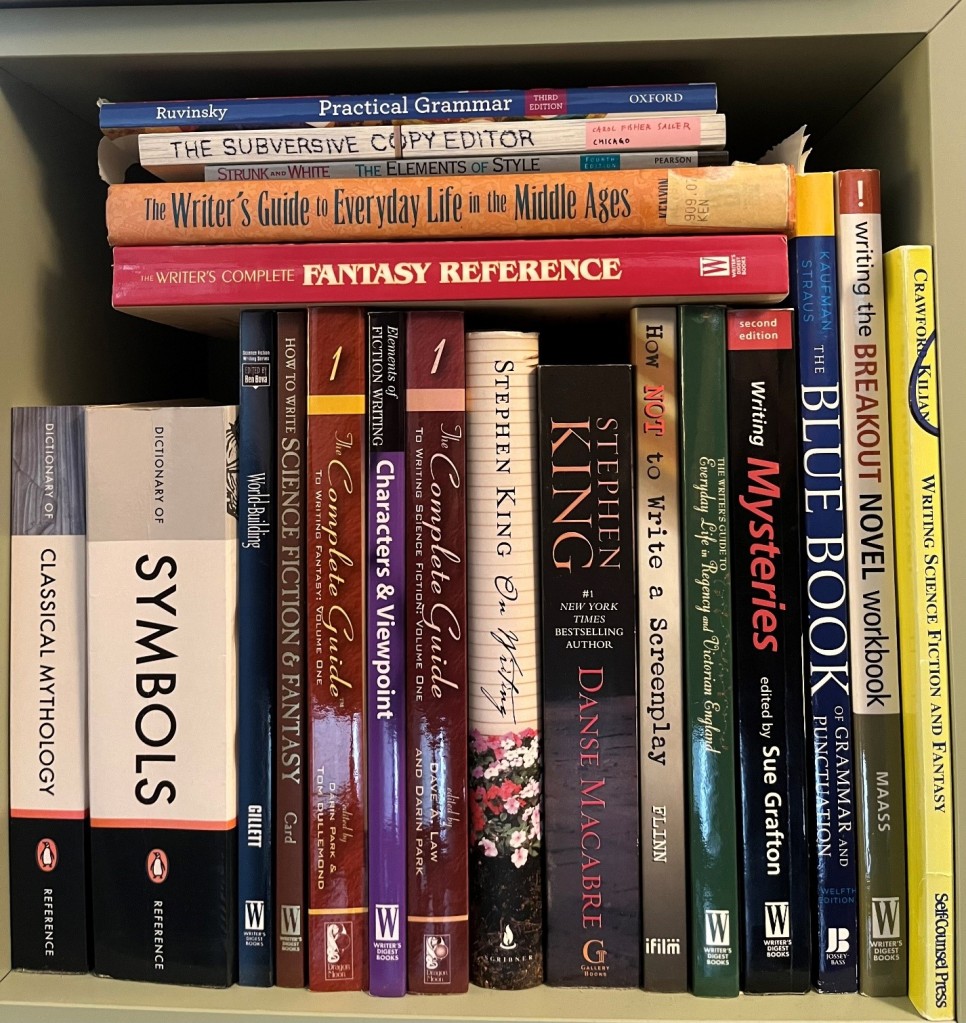

I have a special interest in genre fiction, where it’s not enough to say your orcs carried swords; readers of fantasy fiction will want to know what kind. If your characters have gills and scales, they cannot live in a desert. If your planet is mostly mountains, how do the inhabitants feed themselves? Writers and editors don’t need PhDs in medieval studies or astrophysics, but they do need to be accurate enough that readers won’t be thrown out of the story. As Ben Bova, the late science fiction editor and author, once put it, “if the effort is there, it lends a coherence and substance to a story that can never hurt.” Nothing is as romantic and mood-setting.

Everyday Life in Regency and Victorian England from 1811–1901 (1998) by Kristine Hughes is perfect for writers of romance, Holmesian mysteries, and generally magical worlds. Hughes offers details about everything from plumbing to “wife-selling” (apparently a thing), travel to etiquette. Every chapter also includes a bibliography. A great resource if you’re feeling really committed to getting the details right.

Fun fact: Servants often sold used tea leaves to tea vendors, who redried the tea leaves on heated plates and redyed them, and then sold them as “new tea.”

The Writer’s Complete Fantasy Reference: An Indispensable Compendium of Myth and Magic (1998), edited by David H. Borcherding, is a soup-to-nuts collection of essays about the things you’ll need to know to write or edit fantasy. Essays include “Traditional Fantasy Cultures,” and topics include magic, commerce, and mythical creatures, as well as guides to castles, armour, and dress/costume. Diagrams, maps, and pictures are included.

Fun fact: Forms of medieval divination included cephalomancy (reading the head of a donkey, goat, or other animal) and onychomancy (symbols and signs revealed by sunlight on fingernails).

The Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life in the Middle Ages: The British Isles from 500 to 1500 (2000) by Sherrilyn Kenyon covers everyday life in a medieval castle—from food to medicine to festivals—in gorgeous detail. My favourite chapter is “God & War,” which surveys the structure of the church and its saints and offers short histories of the Crusades. Kenyon also reviews the various peoples of the era, and the book includes short bibliographies.

Fun fact: A common treatment for baldness was to rub goose droppings over the bald area.

Pro tip: Library sales are a great place to shop for books.

The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols (1997) is written by Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant. Anyone who’s read Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (2003) knows the power and magic of symbols, which can be codes, or guides, or magical runes. It’s important to check that authors aren’t accidentally co-opting another culture’s symbols and assigning them new meaning; authors may also accidentally use a symbol they consider benign, but which actually has naughty or nasty connotations.

This article was copy edited by Jennifer D. Foster, a Toronto-based freelance editor, writer, and mentor. Her company is Planet Word.

Thanks, Amanda, for all the excellent resource suggestions 🙂

LikeLike