by Indu Singh

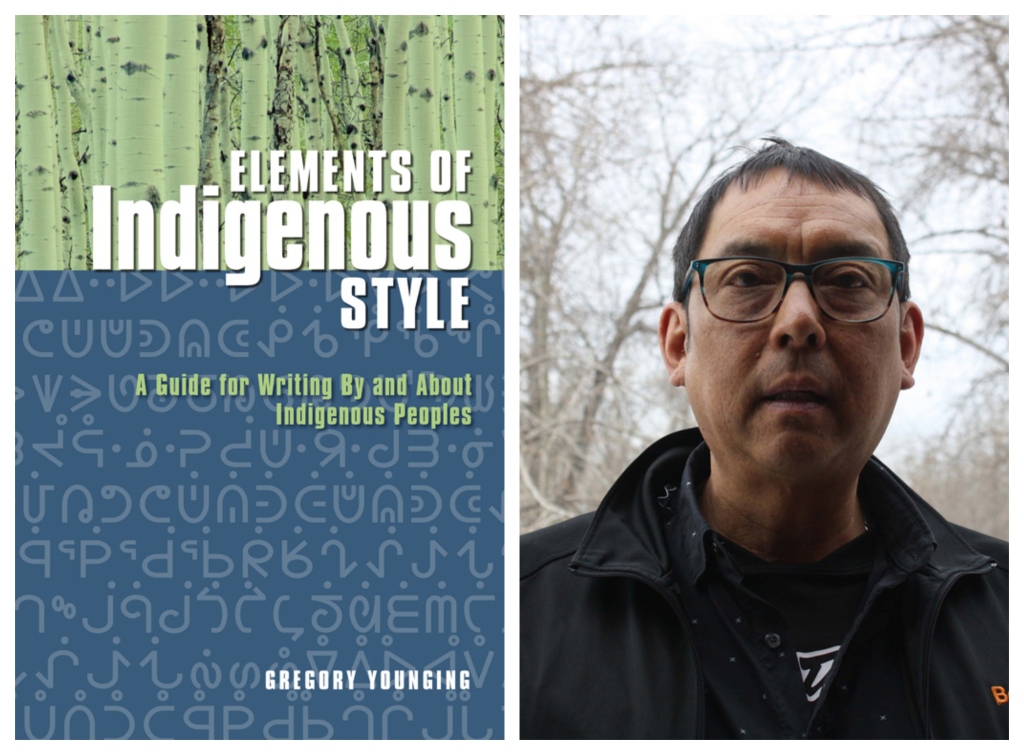

Exactly one year ago today, members of Editors Toronto had the privilege of hearing Gregory Younging speak about his recently published style guide, Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples, at a regular monthly Editors Toronto program meeting. The standing-room-only program was one of our most popular to date.

Gregory Younging passed away on May 3, 2019. The executive of Editors Toronto was profoundly saddened by this news and issued a statement at the time. We publish this book review to honour his memory and the important work he did, and to mark the one-year anniversary of his presentation to Editors Toronto.

Gregory Younging—publisher, editor, poet, educator, and member of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation in northern Manitoba—is known for his groundbreaking advocacy of Indigenous issues and his enduring legacy of nurturing Indigenous writing and publishing in Canada. In Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples (Brush Education, 2018), he assesses Indigenous literature and publishing from the perspective of Indigenous Peoples. The result is a book of 22 editorial principles that guide readers through a new approach to writing and editing material with Indigenous content.

Younging believes it’s high time to decolonize Canadian English—a trend that he points out is already underway. Problematic terms such as primitive and heathen have largely been dropped from usage, while others like land claim and Native are increasingly becoming outdated.

But inappropriate expressions aren’t the only offenders. Even seemingly neutral words like artifact, tribe, and myth, he warns, can be used in ways that undermine Indigenous cultural and political interests. (He suggests replacing these ambiguous terms with more precise ones like artwork, nation, and knowledge, respectively.)

Younging also recommends more capitalization than traditional style guides advise. Capitalization can restore respect and legitimacy to Indigenous governmental, social, spiritual and religious institutions—thus, Potlatch, Elder, Longhouse, Traditional Knowledge, Oral Traditions, Protocols, Totem Poles, Sweat Lodge, and so on. For similar reasons, he encourages writers to use traditional names for Indigenous Nations—“the names…that Indigenous Peoples use for themselves”—and their appropriate spellings. So, for example, the Iroquois reclaim their original name of Haudenosaunee, and the Mohawk once again come to be known as Kanien’keha:ka.*

Since the 1990s, editing protocols have been steadily moving toward more inclusive language and giving people control over how to represent themselves—that is, to tell their own stories. For example, major publications now endorse the singular they. But there may be less agreement on the capitalization approach Younging suggests. His list of words to be capitalized isn’t exhaustive and has the potential to introduce inconsistencies in how different publications apply this principle. Younging acknowledges that the guide is a work in progress and, as such, will require regular updating.

Even as he encourages approaching Indigenous style systematically, Younging is careful to stress process rather than passive rule-following: “Indigenous publishing is about finding your way through, grounded in respect for Indigenous ways of being in the world and for Indigenous Peoples as distinct from one another… . Finding your way through requires thought, care, attention, and dialogue. It requires working with people.”

Finding your way also requires working in culturally appropriate ways. Historically, mainstream publishing dictated that the first person to write down Traditional Knowledge and Oral Traditions could claim copyright ownership. That the information was Indigenous cultural and intellectual property and wasn’t free for the taking was never taken into consideration. Traditional Knowledge and Oral Traditions have sacred significance for Indigenous Peoples, and Indigenous Protocols—Indigenous Laws—govern how, when, and even by whom Traditional Stories can be told. Some stories can be told only “by certain families or Clans, or only by women or men, or only during certain seasons,” Younging writes.

Younging reminds readers that Indigenous Peoples in Canada have endured a painful history of genocide, colonization, and the atrocities of the missionary and residential school era. So, handling the publication of Indigenous trauma with sensitivity and care is extremely important. This history makes the last principle in the guide especially poignant. It explains that Indigenous cultures aren’t relics but are very much alive. Despite a century of forced assimilation, Indigenous Peoples continue to practise artistic and cultural traditions that link them to their ancestors. Younging reminds editors and publishers to avoid describing Indigenous Peoples in the past tense and instead show them as distinct cultures rooted firmly in the present.

Elements of Indigenous Style is targeted to writers, academics, students, and journalists, as well as editors and publishers—in short, anyone interested in works by and about Indigenous Peoples. Written in a scholarly yet intimate voice, the guide encourages readers to be alert to the power of language, especially when it’s used to marginalize people who are vulnerable and oppressed. Younging also reminds writers and editors to collaborate with the Indigenous Peoples at the centre of a work and not appropriate the Indigenous voice but to show respect by observing Indigenous Protocols. Although the historical and political focus of the guide falls squarely within the Canadian context, the values the book advocates have universal application.

*Other variations for this spelling include Kanien’kehá:ka and Kanyen’kehà:ka. The spelling used in this article appears in Elements of Indigenous Style.

Indu Singh is a Toronto-based writer and editor. She is the vice-chair of Editors Toronto.

This article was copy edited by Michelle Schriver.