by Jaye Marsh

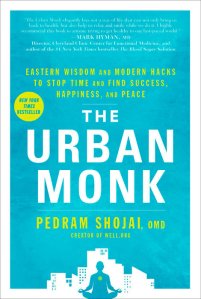

In general, North Americans are stressed, overweight, stuck to our desks, and disconnected from the world we live in. With The Urban Monk, Pedram Shojai attempts to help us address these issues by offering tools, including online resources and email support, to “hack” a more balanced lifestyle.

I really wanted to like this book, but it was a challenge. The writing style is the culprit here, not the content. I was pulled out of the messaging, and the information to be gleaned here, too many times not to mention it.

The Urban Monk reads as if the publishers are Millennials/Generation Y or whatever generalization is currently en vogue. Our supposed readers are the ever-taxed and ever-busy 30- to 45-year-olds replete with children, mid-career angst, mortgages, housing problems, and stuff problems, and are in need of a current version of Zen to help them find a way to sanity that allows for who they are rather than completely. To that end, this book has its place, but it ignores a huge segment of depleted populace in need of help: those who don’t live an urban lifestyle. None of the case studies offered in the book take place in non-traditional settings like freelancing, consider people juggling multiple jobs, or explore those facing financial struggles.

Shojai describes himself as a doctor of oriental medicine. He spent four years at a monastery in China and is the founder of Well.org, a company that creates and provides blogs, videos, and print media on health and wellness. He chose to share his tips and health strategies after experiencing frustration with the current allopathic health model of fixing what’s broken (treating illness) rather than a more holistic approach of preventing issues in the first place. Shojai has a sales angle, which may explain his narrow target market, but much of his information is available for free.

His premise is that it’s fine for a monk to get away from all things physical to find peace and balance, but that there must be another way for folks living (stuck?) in Western culture to find a connection to themselves that involves employing their physical selves, not abandoning them.

The trouble, he postulates, is the application of Eastern practices in Western thinking and philosophy. Where the West has fallen down, he argues, is in finding a spiritual connection through the body. Shojai attempts to bridge this gap with his books, videos, and courses. I lament the narrow focus of his target audience; I know plenty of people who aren’t in his nine-to-five suburban model who could benefit from these ideas if they were presented in a more general approach. His hacks are good, the research is relatively sound (the woo-woo pseudoscience often found in these types of books is kept at a minimum), and his support is generous.

Shojai, the self-styled “urban monk,” has found a clever and humorous way of sharing and teaching that makes this bridge achievable for the average North American desk-warrior. This book, accompanied by free guidance emails, videos, and web resources, hands us a blueprint to apply Eastern wisdom to our lives, using modern hacks. He invites all of us to become urban monks by waking up, paying attention to where we spend our time and our limited energy, and considering how we manage and refill those diminishing resources.

The main concepts are not new, but the presentation here mostly does its job: Shojai uses anecdotal stories to illustrate problems, to which most of us can relate, and then continues to refer back to these familiar scenarios as he shares a different way to approach each situation.

Most of the language is well-crafted, peppered with some casual remarks for humorous effect, and the book as a whole has good flow. And then I was blindsided with random profanity. I don’t have an issue with good old-fashioned Anglo-Saxon expletives, but they seem out of character when compared to the context and vocabulary, even with the casual tone the book was obviously going for. It jarred.

I watched some of Shojai’s videos from his community support blog to see if he really spoke like this or if the profane language was an editorial decision. Throughout his presentations are plenty of scare quotes (“pop in the clutch,” “high gear”), some questionable phrasing (“connect up with”), and casual language (“ain’t,” “sucks,” “right?!”), but the terms shitshow, fucking, and the liberal use of the word shit were not in evidence in his speech. In my opinion, the profanity added nothing of value to the book and seemed a blatant but poorly executed attempt at branding.

Copy editing issues also proved distracting, along with a few fact-checking errors (no really, slavery did exist before Queen Elizabeth I and Columbus [page 123]). Also bothersome, the mommy guilt-tripping is in evidence when Shojai shares the case of Ann, who has low self-esteem: “Her problems could be traced back even further. Ann was born a C-section baby. This means she wasn’t exposed to the vital mix of good bacteria that was supposed to be transferred by mom’s vaginal canal…. What this did was create an environment where the wrong types of bacteria took hold in Ann’s gut. She was a colicky baby who hardly slept. Mom didn’t breastfeed…” (page 120). While these facts may be true, they are hardly causative of her self-esteem issues. If this argument is taken to its logical conclusion, it might lead one to postulate that a child’s problems should be blamed on a choice mom had to make. Never a nice message.

Shojai also offers time-management tips for traditional nine-to-fivers. He doesn’t make much effort in suggesting how people might apply his suggestions when they work in what’s laughingly called the “flexible economy”—another term for people who work “not nine to five” and who work “more than one job so you can eat.” Many of us who freelance might have benefitted from at least one case study reflecting our reality.

That being said, Shojai’s book and supporting seven-day course materials focus on typical issues we all share: food, exercise, stress, time, sleep, energy, and focus, and most of the tips are actually within reach of those needing help in these areas. In fact, his tips recall the strategies addressed at Editors Toronto’s September 2017 branch meeting on time management. His suggestion to reconnect to the earth mirrors the philosophy of one of my favourite artists, Hundertwasser: a delightfully eccentric architect in Vienna who fought against flat surfaces, crying that they were meant for wheels, not feet! The Urban Monk (that being the reader) is encouraged to get barefoot and feel the undulating ground under their bare feet.

I appreciated the book’s message and hacks, despite not feeling reflected in its pages and despite being put off by the obviousness of the casual language. I’ll keep watching the videos, if I have time. And now I must get up off my chair and move, just like the author told me to!

Jaye Marsh is a professional flutist, editor, and designer in Toronto. Her passions are music, knitting, and words—in no particular order. http://www.theredscribbler.com

This article was copy edited by Lexie Hofer.