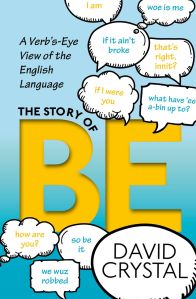

(Oxford University Press, 2017)

By Christine Albert

Some words are so familiar that it feels as though we instinctively know what they mean. And when we don’t, we use a dictionary to read its definition and determine how it can be placed alongside other words to form cohesive narratives. But how often do we think about the history behind the word itself, the changes it’s gone through and the nuances it provides the English language and the topics being discussed?

In The Story of Be: A Verb’s-Eye View of the English Language, David Crystal examines the verb to be, highlighting the meanings created and used throughout its long history. A linguist, editor, and prolific writer, Crystal is well-known for his research in English language and has published over 100 books and almost 500 articles on topics such as religious language, Internet language, and clinical linguistics. Each chapter of The Story of Be is dedicated to a specific function of the verb, ranging from the more philosophical (“existential be”) to the scatological (“lavatorial be”). In the latter chapter, for instance, Crystal muses on the origins of the saying “Have you been?” to denote using the washroom, delving into past literature to see when this phrasing began. Alongside these explanations are numerous examples from a variety of sources, including literary, pop culture, religious, and technological. And sprinkled throughout the book are text boxes that focus on the history of the word’s various tenses, showing their development from Old English to modern times and their regional uses.

It seems like a daunting task to document the history of this ubiquitous verb, but Crystal focuses his exploration. Early on he states, “My approach in this book is linked to lexicography, rather than to logic or philosophy, and takes the OED definitions as a starting-point” (26). In each chapter, he outlines a specific function of to be, explaining the idioms associated with it and sometimes its social context. For instance, the chapter on “sexual be” (“I’ve been with someone”) not only examines the birth of this absolute use but also relates it to the sensibilities of the Victorian society in which it was born. In the panels, he discusses both regional and class differences in use of the various verb tenses. For example, the use of were as a singular form and was as a plural form was popular in the north of England in the seventeenth century and provided a way for people to determine whether a speaker was educated or not. But Crystal points out that while this usage is still not standard, it has lost its connection to lack of education, since it’s now used by well-educated people from certain regions in which it is still popular. This inclusion of sociolinguistics in his lexicographical discussion emphasizes that one cannot truly separate words from those who use them.

One difficulty in writing about to be, Crystal notes, is that it can be difficult to draw lines between meanings. For the most part, he does a good job at reducing overlap. While the chapters on “existential be,” “identifying be,” and “membership be” may at first glance seem almost the same, he emphasizes the subtle differences in meaning. That being said, a few of the functions discussed are too similar to warrant separate chapters. For example, the focus on puns in the “musical be” chapter could have been included in the chapter on “ludic be.” But for the most part, Crystal avoids repetitious discussions.

One of the most important messages in this slim volume is that being overly prescriptive about grammar can be detrimental not only to language growth but also to how we view certain groups of people. In the chapter on “repetitive be,” Crystal states that people who use the “is is” construction are sometimes “criticized—though not by linguists—as ‘lazy,’ ‘careless,’ or ‘ungrammatical.’ I view them as a perfectly normal feature of informal spontaneous speech” (101). The “quotative be” (“is like”), reviled by many language purists, actually has provided people with a new narrative option, he argues, because it is more general in nature than other dialogue tags. It can indicate all manners of speech, thoughts, gestures, and facial expressions. In addition, throughout the book he gives examples of regional uses of to be that do not follow rules of “proper” grammar but have importance to the speakers. These examples serve as reminders that to deny certain uses of to be is to deny the importance they play in specific circumstances or for particular groups of people.

The Story of Be will interest anyone fascinated by language history and growth. Crystal’s exploration of the verb may also be pertinent to those editors and writers who work with historical narratives, since his discussion of uses throughout time can help them ensure that the dialects portrayed in their works are accurate and believable.

While this book may be short, coming in at just under 200 pages, it highlights the vastness of this important two-letter word.

Christine Albert is an editor and indexer specializing in fantasy and literary fiction, business materials, and humanities and social science works. She holds a postgraduate certificate in publishing from Humber College and is completing her certificate in editing from Simon Fraser University.

This article was copy edited by Ambrose Li.