By Alanna Brousseau

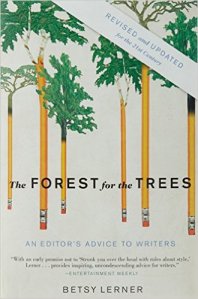

“No matter how beleaguered the world of editing has become,” writes Betsy Lerner in The Forest for the Trees: An Editor’s Advice to Writers (2010), “no matter how short a book’s shelf life in today’s market, no matter how Kindled, downloaded, or digitized, none of us can ever forget the feeling of first discovering the majesty of reading.”

Lerner, an editor turned author turned literary agent, has two books under her belt and a third, The Bridge Ladies, forthcoming in May. I was introduced to Lerner after enrolling in one of my first editing courses in the publishing program at Ryerson University. Her first book, The Forest for the Trees, was one of two primary resources we drew inspiration from over those fast-paced few months. Lerner’s dry wit and self-deprecating humour were invigorating—a far cry from the polite prose we had been reading up until that point.

I did some digging later and stumbled upon Lerner’s blog, and I have been a devout follower ever since. Her posts, often whimsically titled (“You’d Be a Wing in Heaven Blue”), contain the same caustic humour that was the hallmark of The Forest for the Trees. Lerner frequently engages with her readers by posing questions to them at the end of each post. As a result, the comments section has become a lively community where writers encourage each other in their respective endeavours and offer congratulations when the hard work finally pays off.

When I discovered that Lerner worked with musician, artist, poet, and author Patti Smith on one of my favourite books, Just Kids, she secured her place in my mind as Editing Superstar. She became my younger, cooler, infinitely more relatable Max Perkins. Lerner was someone I aspired to be like, and her advice to young editors and writers alike struck me as both tangible and timeless: “The best editor is a sensitive reader who is thinking with a pencil in her hand.”

The Forest for the Trees is an excellent resource for those people who, like me, are new to the field, and I’m grateful for having been introduced to this book early in my editorial career. The first half of the book navigates the author-editor relationship—a coupling that can be as equally fraught as it can be fruitful, depending on the editor’s approach. In this first section, Lerner introduces the reader to a host of author personas that editors will inevitably meet over the course of their careers (“The Ambivalent Writer,” “The Wicked Child,” “The Self-Promoter,” and “The Neurotic”), and she gives invaluable advice about how to successfully navigate each personality.

The second and final part of the book explores the publishing process as a whole, with Chapter 9 (“What Editors Want”) explicitly addressing the role of the editor. The importance of establishing and maintaining a healthy author-editor relationship remains a recurring theme throughout the book, and Lerner recommends that the editor begin to build trust with the author from the outset:

In the most productive author-editor relationship, the editor, like a good dance partner who neither leads nor follows but anticipates and trusts, can help the writer find her way back into the work, can cajole another revision, contemplate the deeper themes, or supply the seamless transition, the telling detail.

Lerner recommends, therefore, that editors spend time complimenting their authors on their strong points before pockmarking a manuscript with revisions. Commending an author on the work’s strengths is an excellent strategy that helps the author and editor get off on the right foot. This approach also helps disarm and prepare the author for the hard work ahead. Being diplomatic is important; in order to foster a healthy relationship between author and editor, the editor must suggest changes rather than demand them.

In the final section of “What Editors Want,” Lerner recalls the halcyon days of book publishing in which editor and author would meet regularly—often over a cocktail or two—to discuss and review the latter’s book. Those were the days when Perkins was in his prime; when an editor’s job description included addendums like “friend, confidante, money lender, and minder.”

This got me thinking: I have never physically met the majority of my clients, and most, if not all, of my correspondence is conducted over email. I often wonder if anything is lost by not meeting clients face to face. Of course, meeting in person isn’t always possible; when it is, it seems like making the extra effort could benefit the author-editor relationship in myriad ways.

Email communication is arguably more efficient and likely less expensive than meeting face to face (martinis aren’t cheap!), but every now and then, like Lerner, I find myself romanticizing this bygone era of book publishing. It might be time to revisit Perkins’ biography.

Alanna Brousseau is a Toronto-based freelance editor and writer. When she’s not on the clock, she enjoys reading and writing poetry, tinkering with her 35mm cameras, and going to the movies as often as possible.

This article was copy edited by Christine Albert.

Alanna, I don’t get to meet too many authors face to face either, but I have learned over the years to arrange at least one phone call somewhere along the way if possible, at least at the beginning of a project. We don’t even have to talk about the project much—just getting to know each other a little bit is incredibly valuable. The most productive editor-author relationship I was ever a part of started out VERY badly, was put back on track by a good long phone call, and was sustained and nurtured by regular phone calls over the months we worked together. One relative short phone call with the author on a more recent project (maybe 10 minutes?) gave me enough information (about the author’s expectations of me as the copy editor, about the project as a whole to date, etc.) to provide the right level of copy editing and to query appropriately. I don’t have occassion to work directly with designers very much these days, but when I did, I always called first or as a follow-up to whatever I might have sent by email (sample, marked-up ms, question). (You know, you’ve made me think I should write a blog posting of my own on this topic!)

I started working as an editor in the early days of email, so communicating by telephone doesn’t seem as foreign or unusual as it might to others. On the issue of communicating by phone in general (something which seems to be on the decline), and on the skills for effective phone communication, I now follow an excellent blog by Mary Jane Copp, aka the Phone Lady: http://thephonelady.com/blog.

LikeLike

So I did in fact write a blog post about one of my phone stories: http://thephonelady.com/the-second-call/. Others to come perhaps!

LikeLike

I missed this when it first came out, Alanna, but I wanted to say how much I enjoyed it. The relationship side of editing gets short shrift in a lot of training materials for editors, and it’s as crucial as grammar IMHO.

Another good resource on author-editor relations (there are not very many!) is Barbara Sjoholm’s Editor’s Guide to Working with Authors. There’s a good write-up of it on Editors Kingston member Ellie Barton’s blog “Editors Reads”: ghttps://editorsreads.me//?s=forest&search=Gogbara

Apparently, there’s a film about Max Perkins coming out next week, starring Colin Firth (with Jude Law as Thomas Wolfe). Perhaps Editors Toronto needs to organize a movie night? ;-p

LikeLike