By Whitney Matusiak

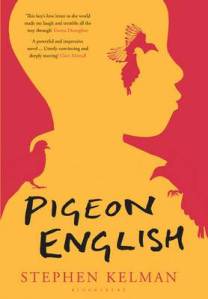

Author Stephen Kelman grips readers and deftly conjures compassion with the use of a culturally and socially magnetic dialect in his debut novel Pigeon English (2011).

the use of a culturally and socially magnetic dialect in his debut novel Pigeon English (2011).

Set in a rough London estate, Pigeon English is a modern-day coming-of-age tale with dark leanings centring on the gang-related death of a young boy. With childlike but remarkably poignant humour and honesty, Ghanaian-born Harri investigates the murder with his best friend Dean. With hints of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and Miriam Toews’ The Flying Troutmans, readers are engaged in thought-provoking social questions, and Harri’s boundless curiosity and sympathy give way to a tale that is as beautiful as it is heartbreaking.

The success of Pigeon English is undoubtedly a result of Kelman’s extraordinarily imaginative and realistic characters. Kelman takes a literary risk, using a lot of informal language, and the title of the novel evokes this language play. Kelman brilliantly uses interjections of West African Pidgin English, or Guinea Coast Creole English, to breathe life into Harri and the supporting characters.

Also known as “coastal jargon,” this form of Pidgin English arose in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries during British-dominated slave trade along the Atlantic coasts. Kelman’s use of Pidgin English allows readers to hear characters admire and admonish in a language that has been historically cultivated and colloquially blended by the people of the Americas, Europe, and West Africa. Here are some of the expressions that appear in the book:

“adjei”: an expression of mild consternation, irritation, lament

“bogah”: a slang term for a gangster

“dey touch”: mad, insane, mentally ill

“gowayou”: the contraction of “go away you”

“idey”: nearly

“rarse”: a multi-purpose term of emphasis to express amusement, surprise

The Pidgin English is not the only deviation from “proper” English in Kelman’s novel. Combine it with London lingo, and you’re happy to have the glossary at the back of the book to help you out. There are other examples of slang and informal (sometimes insensitive) uses of language that, in context, help accurately describe Harri’s community, family, and school from the point of view of an 11-year-old, underprivileged Ghanaian immigrant. And just like any child who feels the emotional extremes of happiness, sadness, and surprise, Harri uses a small but powerful arsenal of words that make recurring, if not catch-phrase-like, appearances, such as:

“bo-styles”: cool

“manky”: gross

“hutious”: scary, frightening

Kelman and his editing and publishing team could have opted for linguistic and grammatical propriety, but at what cost? The grammatical slips and trips add vibrancy and culture that would have been otherwise hard to convey without being insincere or obvious. It’s Kelman’s selective and strategic use of Pidgin English and other flagrant uses of language that give an authentic flavour to his characters and their development, without overwhelming the reader. Pigeon English teaches writers and editors alike the importance of sensitive editing for the purposes of story and character development. The beauty behind the oddball turns of phrase is the genuine voice behind every sentence, and the knowledge that it’s building more than a character; it’s also building a community and a history.

Kelman’s story of a young boy’s curiosity and compassion transcends not only its genre, but also the “rules” of grammar and language, whatever those are.

Whitney Matusiak is a freelance writer and editor for Jean Marie Creatively, providing copywriting, substantive editing, and copy editing services for corporate, academic, trade, and lifestyle publications.

This article was copy edited by Jeny Nussey.